AfCFTA, AIDA: Africa’s dual pathways to economic integration, industrial development

In a bid to promote intra-African trade and Pan African industrialization, the AU has continued to evolve various normative frameworks aimed at the successful realization of its vision “for an integrated, people-centred, prosperous Africa,” as enshrined in Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want

Economic integration was one of the central objectives for the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, by Heads of State and Governments of newly independent African states. Over 50 years later, economic integration has remained at the center of the agenda of OAU’s successor, African Union. It was against this backdrop that the 1980–2000 Lagos Plan of Action for the Economic Development of Africa (LPA) was adopted by the defunct OAU in 1980, to increase Africa’s self-sufficiency by maximizing its own resources.

Moreover, in 1991, the Abuja Treaty created the African Economic Community (AEC) whose primary objective was the establishment of a continental economic community, culminating in an African Common Market, whose building blocks would be the Regional Economic Communities (RECs). The actualization of the AEC would also lead to the establishment of an African Central Bank as well as an African Monetary Union, amongst other financial institutions, aimed at enabling Africa’s economic integration.

It was in a bid to promote intra-African trade and Pan African industrialization towards attaining the major objectives of African Economic Community (AEC), that the AU has continued to evolve various policy frameworks that will facilitate the successful realization of its vision “for an integrated, people-centred, prosperous Africa,” as enshrined in Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Agenda 2063 is the 50-year strategic blueprint for transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future.

However, true economic integration will never be accomplished in Africa without boosting intra-African trade, through enhanced harmonization and coordination of trade liberalization and industrial development. The AU has thus developed many frameworks aimed at fast-tracking its economic integration and industrial development policies under the First Ten Year Implementation Plan (FTYIP) of Agenda 2063 (2013 – 2023).

These normative frameworks include the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement; the Action Plan for the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa (AIDA); Program for the Infrastructural Development of Africa (PIDA) and the Action Plan for Boosting Intra-African Trade (BIAT).Others are the Africa Mining Vision (AMV); Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA); African Agri-business and Agro-industries Development Initiative (3ADI); African Integrated High-Speed Railway Network (AIHSRN); as well as the AU Commodities Strategy and AU SMEs Strategy, amongst others.

All these agendas are targeted at achieving Goal 1, Aspiration 2 of Agenda 2063, which strives to accelerate “progress towards continental unity and integration for sustained growth, trade, exchanges of goods, services, free movement of people and capital through establishing a United Africa and fast tracking economic integration through the Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA).”

AfCFTA: Creating one African market

Although Africa is home to a vast of array of largely untapped natural and mineral resources, including huge oil and gas reserves as well as a largely youthful population of 1.2 billion people, with a combined GDP of USD3.4 trillion to boot intra-African trade is merely 15% while the continent’s share of global trade is a paltry 3%.

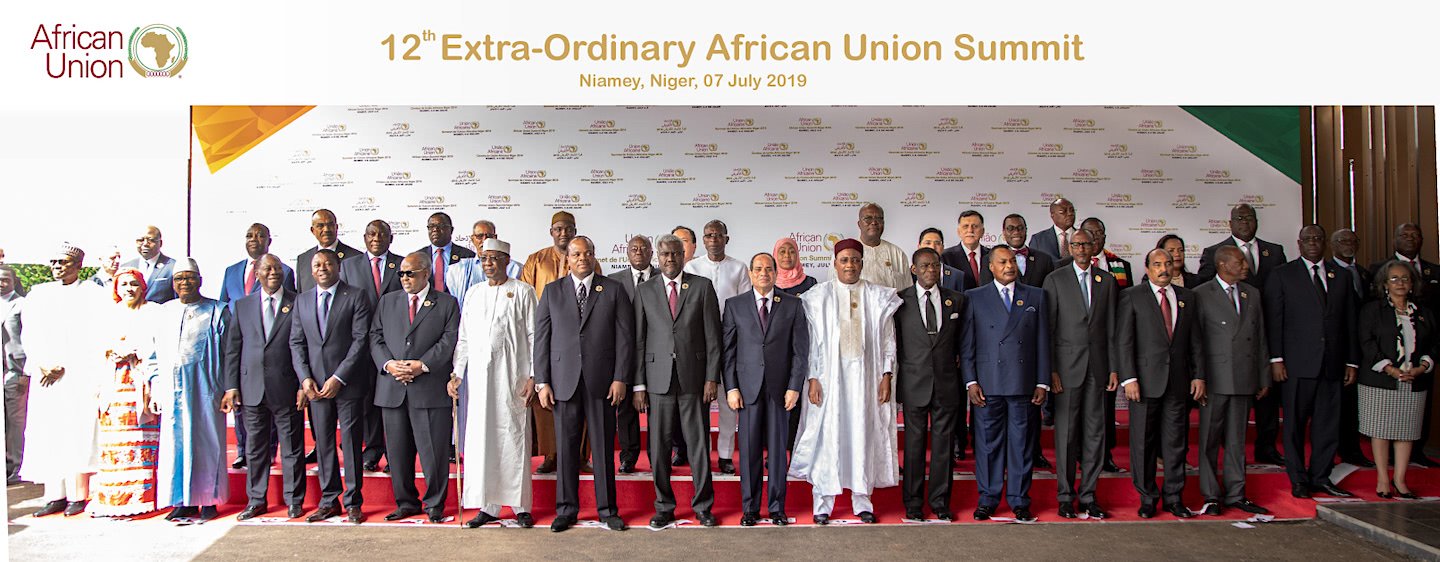

Operationalized at the 12th Extraordinary Summit of Heads of State and Governments of the AU in July at Niamey, Niger, the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is the biggest opening for boosting intra-African trade yet as well as being the largest free-trade area in the world – in terms of number of countries – since the formation of World Trade Organisation. AfCFTA is also one of the flagship projects of the First Ten Year Implementation Plan of the AU’s Agenda 2063. It envisions a single, liberalized continental market for goods and services as well as guaranteeing the free movement of business persons across the continent.

Rongai Chizema, chief technical advisor and head of AIDA Implementation and Coordination Unit (ICU) at the Africa Union Commission (AUC) says as Africa’s 1.27 billion people was projected to rise to 1.7 billion by 2030, the figure of the continent’s middle class would also rise to 600 million by 2030, with an aggregate GDP of between US$2.1trillion and US$3.4trillion, depending on source of statistics, boosting intra-African trade in the process.

“Large and dynamic AfCFTA market can boost intra-African trade while trade with the rest of the world will double between 2012 and 2022. Large size with liberalization provides large economies of scale, promotes efficiency and generates locational advantage,” Chizema told a select group of African business journalists attending a 3-day media orientation workshop organized by the AU, under the theme: “Building Media Awareness on Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa (AIDA) and related strategies: Industrial Policy Literacy,” held last week in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The training was organized by the AUC’s Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) in collaboration with its Directorate of Information and Communication (DIC) and the German Development Cooperation (GIZ).

While also addressing the group of journalists on AfCFTA’s journey to date, Million Habte, senior expert on trade at the AUC’s AfCFTA unit, said the first phase of the AfCFTA negotiations had covered issues to do with trade in goods and trade in services while the second phase covered issues to do with investment, intellectual property rights and competition policy, adding that the key institutions involved in AfCFTA negotiations were the AfCFTA-Negotiating Forum (AfCFTA-NF), Senior Trade Officials (STOs) and African Union Ministers of Trade (AMOT).

“The 1st meeting of the AfCFTA-NF was held in February 2016, followed by the 1st meetings of the STO and AMOT, both of which were held in May 2016. The 28th Ordinary Session of the African Union Heads of State and Governments held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in January 2017; it mandated His Excellency Issoufou Mahamadou, President of the Republic of Niger to be the Leader of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Negotiations. During the 30th Ordinary Session of the African Union Heads of State and Governments held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in January 2018, the name African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) was adopted,” Habte narrated.

While sharing a summary of key outcomes of the AfCFTA negotiations, Mr Habte said the objectives and guiding principles for AfCFTA negotiations already adopted were: modalities for tariff liberalization with the ambition of liberalizing 90% of tariff lines over a period of 5 to 10 years, depending on the categories specified; as well as modalities for liberalisation of trade in services with a hybrid approach of schedules of specific commitments accompanied by regulatory cooperation.

Other adopted objectives and guiding principles for AfCFTA negotiations were the agreement establishing the AfCFTA together with 3 protocols by the AU Assembly, which was adopted on 21 of March 2018, in Kigali, Rwanda as well as 12 annexes to the protocols, which were adopted by the Assembly on 1 July 2018, in Nouakchott, Mauritania.

AIDA: Accelerating Pan African industrialisation

The Plan of Action for Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa (AIDA) programme is the AU’s main normative framework for continental industrialization, endorsed by the Summit of the Heads of State and Governments at their January 2008 Summit; the Summit was themed: “The Industrialization of Africa,” which was seen as a mark of African leaders’ renewed commitment to the industrialization of the continent, in both short and long-terms

In pursuance of this directive, the AU Commission, in collaboration with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), developed a strategy for the implementation of the Plan of Action, across seven programmatic clusters, namely: Industrial policy and institutional direction; Upgrading production and trade capacities; Promote infrastructure and energy for industrial development; as well as Industrial and technical skills for Africa’s development. Others are Industrial innovation and technology systems and research and development; Financing and resource mobilization; and Sustainable development for responsible industrialization.

Unfortunately, there has been a slow implementation of AIDA over the first ten-year period (2008-2018). “This has been attributed to lack of financial and human resources to coordinate this implementation. Lack of an institutional mechanism to drive the implementation and coordination of AIDA has stalled the programme to date,” said Chizema. However, in May 2018, the AIDA Implementation and Coordination Unit (ICU) was set up at the AUC’s Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) with the mandate to “provide oversight, coordination and technical advisory responsibility to AIDA implementation and other related continental frameworks.”

Speaking on Africa’s journey towards industrialization, Mr Chizema said unlike other developing regions of the world, Africa had experienced what he called “a relative deindustrialization” with the share of manufacturing value added to Africa’s GDP falling from 12.8 percent in 2000 to 10.5 percent in 2016. “This does not mean that Africa’s industrial output is lower than 20 years ago but the pace of industrialization was slower than other sectors and far lower than that of other developing regions. For instance, Africa’s share in the global Manufacturing Value Added (MVA) has stagnated at around 1.5% between 2000 and 2013 while developing Asia’s share has almost doubled to 25% over the same period,” he adds.

Chizema said because overall the region had continued to underperform across many areas of the basic requirements of competitiveness, i.e physical infrastructure and social infrastructure (health and basic education), more than half of the 20 lowest ranked countries in the Global Competitive Index ranking of 2014/2015, were African countries. He added that 50% of AU Member States had recorded negative MVA per capita growth while only 5 countries had experienced a strong industrialization with an MVA per capita growth above 4 % per annum, within the period.

“Africa remains heavily dependent on resource-based manufacturing, which is an indication of both its low level of economic diversification and low level of technological sophistication of its production. According to the AfDB, African economies rely on commodities that account for more than 70% of their exports, whilst strongly importing manufactured goods that account for over 50% of their import bill. Industrial GDP remains very low across Africa and the structure of manufactured exports is still resource-based and low technology,” Chizema said.

PIDA: Improving Africa’s infrastructure for economic integration

Other than the duo of AfCFTA and AIDA, there is another very strategic framework at the centre of Africa’s quest for economic integration and industrialization drive: the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA). Designed as a successor to the NEPAD Medium to Long Term Strategic Framework (MLTSF), PIDA is a strategic framework for the development of a continental infrastructure in the areas of energy, transport, ICTs as well as trans-boundary water resources, aimed at facilitating African integration, by 2040.

No doubt, Africa’s poor infrastructural condition is a huge barrier to achieving true economic integration. “319 million people are living without access to improved reliable drinking water sources, 695 million people are living without basic sanitation access, only 34 percent have road access, and 620 million people don’t have access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa,” wrote Landry Signé, a David M. Rubenstein Fellow in the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution.

There are many supposedly ongoing infrastructure projects across Africa under PIDA, being led by various African heads of state such as the Unblocking Political Bottlenecks for ICT Broadband and Optic Fibre Projects Linking Neighbouring States and the SMART Africa Project, being championed by President Paul Kagame of Rwanda; and the Dakar-Ndjamena-Djbouti Road/Rail Project being anchored by President Macky Sall of Senegal. Others are the Construction of Navigational Line between Lake Victoria and the Mediterranean Sea, being led by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt; as well as the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project being led by President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya, amongst others.

AMV: A model for natural resource governance in Africa

Despite Africa’s enormous mineral resources, little benefits seem to accrue to mining communities and national governments across Africa. The Africa Mining Vision (AMV) is the AU’s response to the failure of AU Members States to drive value out of local extractive industries, due to lack of capacity on the part of local investors and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to invest in the extractives and therefore create jobs and wealth that will power local economies, necessary for Africa’s development.

Speaking at the AU media orientation workshop on the topic: “Africa Mining Vision: The Case for a Resource-based Industrialization Path-way,” Paul Msoma of AUC’s Mining Unit said the AMV was adopted by AU Heads of State in 2009, “With the long-term goal of attaining transparent, equitable and optimal exploitation of mineral resources, to underpin broad-based sustainable growth and socio-economic development.” He therefore said AMV wasn’t just about mining, instead about Africa’s development; it seeks to transform Africa’s socioeconomic development.

Mr Msoma said Africa’s “Significant and diverse mineral resources and production, together with its regional markets and the ingenuity of its diverse peoples, provides a powerful combination to realize regional resource-based equitable growth and development and contribute to Africa’s industrialization strategies as well as inter-generational equity. This can only be achieved through the realization of all the mineral linkages, within the guiding framework of Regional Mining Vision, for the upliftment of all of its citizens.”

Towards achieving Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want

Beyond these normative frameworks, the AU has got many other policy frameworks all of which are targeted at expediting Africa’s economic integration and powering the continent’s industrialization drive. Such other frameworks include the Boosting Intra African Trade (BIAT) policy which seeks to stimulate Africa’s market integration and boost intra-African trade, from its current levels of about 15% to 25%, within the next decade; as well as the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) defined as “Africa’s policy framework for agricultural transformation, wealth creation, food security and nutrition, economic growth and prosperity for all.”

There is also the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA) which seeks to strengthen Africa’s ability to produce high quality and affordable pharmaceuticals across all essential medicines; it will contribute to improved health outcomes and the realization of direct and indirect economic benefits. Again, there is a draft AU Commodity Strategy which envisions commodities as drivers for social and economic transformation of Africa as well as ensuring Africa’s commodities become the backbone of the continent’s industrialization agenda.

These and other frameworks underscore the significance the AU accords to Africa’s economic integration and industrial development. “Though abundantly endowed with natural resources, including many industrial minerals and agricultural resources (that is hosting the most arable land in the world), the continent remains food insecure, and poor. This is mainly due to the fact that resources continue to be exported with no local value addition and processing,” Ron Osman Omah of the AUC’s Industry Division told the journalists in Addis Ababa, last week.

“The persistent lack of industrialization is a dent or drag on the African economies, which remain largely dependent on agriculture and unprocessed commodities that add little value. On average, Africa’s industrial sector generates a mere USD 700 of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, which is less than a third of the same measure in Latin America (USD 2,500) and barely a fifth of that in East Asia (USD3,400).”

This further accentuates the need for Africa to integrate and industrialize; until the continent begins to add value to its vast array of raw materials including mineral and agricultural resources, Africa would continue to export its prized raw materials, only for the continent to import them as finished products, at a value that is many-fold the value they were exported. According to Andrew Rugasira, a Ugandan coffee entrepreneur, “When you add value, you retain not just the financial value in the country, but you create jobs, businesses pay more taxes and that is how you develop the economy.”

Most importantly, African governments must invest in R&D in the areas of Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) as well as promote Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET); so as to capacitate local SMEs and industries to produce high-end products for the African market and also for export to various parts of the world. It is worthy of note that without the requisite manpower and skills mix, technologies, innovations as well as enabling policy structures, the continent’s quest to produce products and services that will compete favorably within Africa and globally, will remain a fantasy!

Although Africa constitutes 16% of the world’s population, the continent accounts for only 3% of global trade, and whereas intra-continental trade in America is placed at 47%; Asia (61%) while Europe (67%), intra-African trade is merely 15%. Now that AfCFTA is operationalized, African countries must end the era of protectionism by opening up their borders to people, goods and services from the continent. There must be deliberate policies to promote ‘Made in Africa’ goods to everyone on the continent as well as identify and explore market opportunities in Europe, Asia and the Americas.