OP-ED | The Cost of Capital Is a Public-Health Emergency for Africa, By Serah Makka & Rosemary Mburu

High borrowing costs mean that African governments often must choose between making debt payments and investing in health. This November’s G20 summit – the first to be held in Africa, and the second with the African Union as a permanent member – represents a critical opportunity to create better options.

May’s 78th World Health Assembly (WHA) – the annual meeting of the World Health Organization’s member states – ended on a self-congratulatory note. From an agreement on pandemic preparedness to increases in assessed contributions to the WHO, there were plenty of achievements to tout. But there was an elephant in the room, hiding behind a banner reading “One World for Health” (the event’s theme): the high borrowing costs faced by African countries.

Despite being the world’s youngest continent, Africa bears 24% of the global disease burden. Yet it accounts for less than 1% of global health spending. In 2001, African countries decided to take matters into their own hands, pledging to devote at least 15% of national budgets to health. Yet, more than two decades later, only twocountries have reached that target. On average, governments on the continent allocate a mere 1.48% of their GDP to health, while 37% of health spending comes directly out of citizens’ pockets.

Borrowing costs are a major reason why. Whereas high-income countries borrow at an interest rate of 2-3%, their African counterparts can face rates above 10%. This discrepancy – which reflects investors’ perception of heightened risk in African economies – means that governments on the continent often must choose between making debt payments or buying medicines, hiring doctors, and building health clinics. The cost of capital costs lives.

Consider Kenya’s ill-fated Managed Equipment Services (MES) program, a public-private partnership aimed at enhancing service availability at hospitals through the provision of modern equipment. The program did provide high-tech equipment to many hospitals. But, given the cost of capital for investment, Kenya could not deliver the infrastructure or personnel to use it.

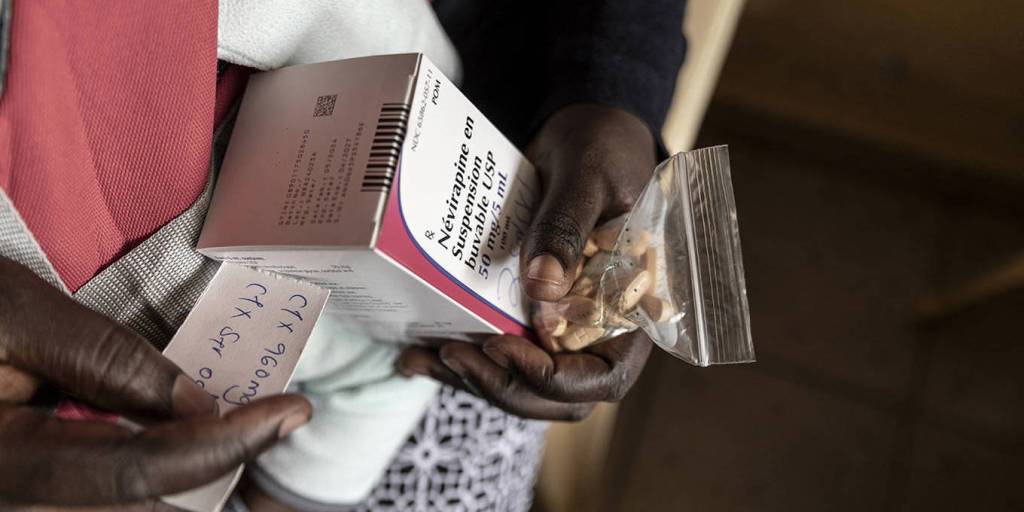

In Ghana, where debt-service costs have left little fiscal space, nearly 75% of the government’s health budget now goes to health-care workers’ wages, leaving little funding for other crucial expenses, from medicines to maternal-health programs. In 2023, a shortage of antimalarial drugs forced some rural clinics to direct patients to purchase the medicine they needed directly from private pharmacies. Many families thus faced a harrowing choice between being driven further into poverty and sending a loved one to an early grave.

For many African countries, high borrowing costs have contributed to dependence on the goodwill of foreign donors. But aid-dependent health-care systems are fundamentally fragile. We saw this during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we are seeing it now, as European countries scale back their development spending to free up space for other priorities, and the United States dismantles its entire aid apparatus, beginning with the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

In Malawi, those cuts have already forced critical programs, such as for HIV treatment and prevention, to scramble for funds. Local NGOs have been forced to lay off outreach workers, and patients with tuberculosis or HIV have gone without care. As one community health nurse in South Africa lamented, “My fear is mortality is going to be very high.”

Africans’ health cannot depend on the generosity of others. Governments must be able to invest in stable, resilient, self-sustaining health systems. To raise funds, Senegal and Zambia are experimenting with “health taxes” on alcohol and sugary drinks. Debt-for-health swaps in countries like Seychelles have shown promise. Nigeria’s diaspora health bonds could unlock billions in financing if they are matched with concessional capital and guarantees from multilateral banks.

Ultimately, there is no substitute for affordable, predictable capital. That is why lowering borrowing costs must be a key priority at the G20 summit this November.

This means, first, tackling structural factors such as outdated international regulations and biases in risk assessments. It also means delivering timely and meaningful debt relief. This will require innovative mechanisms, such as debt-for-health swaps, and increasing the use of pause clauses in existing loans and new debt contracts that allow for debt payment suspension when a pandemic strikes.

A third priority must be to secure continued political support for multilateral health programs – such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria – thereby ensuring continuity in the delivery of the relevant health services. Finally, the G20 must seek to expand African countries’ access to concessional financing for health infrastructure through multilateral development banks.

The G20 is the right forum for these actions. Its mandate includes addressing global challenges, promoting economic cooperation, and fostering global stability. The cost of capital is beyond any one country’s capacity to address, and it is producing a destabilizing global-health emergency. The upcoming G20 summit, the first to be held in Africa – and the second with the African Union as a permanent member – represents a particularly fitting moment for such action.

Within African countries, mechanisms – based on civil-society engagement – for ensuring accountability for how funds are spent are also essential. But the first step must be to free up the funds. To achieve “One World for Health,” all countries must be able to access the means to invest in health care.

Serah Makka is the Africa Executive Director at The ONE Campaign, while Rosemary Mburu is Executive Director of WACI Health. This op-ed article was originally published in Project Syndicate, African Newspage’s publishing partner. The views it expresses do not necessarily reflect African Newspage’s editorial policy.