SOJO | MS Ladies Closing Family Planning Gap in Kano’s Remote Communities

In the remote villages of Kano State, northern Nigeria, a quiet revolution is unfolding — one that is transforming how women access family planning services and reclaim control over their reproductive health.

Every month since 2021, twenty-five-year-old midwife Bahijja Dauda has journeyed twice to hard-to-reach communities of Rano Local Government Area of Kano State to deliver family planning services as part of her “community in-reach” duties under the MS Ladies initiative.

“Each trip, each community, presents me with new experiences and opportunities,” MS Lady Bahijja said, smiling.

On a breezy morning in February 2022, Bahijja boarded a motorcycle to Fansheri, a rural settlement in Rano. Ahead of her arrival, Hajiya Inna, a respected elder, had already spread the word that a lady healthcare provider would be offering free family planning services that day.

“When I arrived around 9:00 a.m., about 50 women were waiting for me under the neem tree behind Inna’s courtyard. They were all there for the free services, with their husbands’ approvals,” Bahijja recalled.

Before she began administering the FP services to her clients, Bahijja’s eyes caught a familiar face among the crowd — a woman she couldn’t quite place. When she approached her, the memory came rushing back, bringing tears to her eyes.

That woman was *35-year-old Maryam Muhammad, whose story of courage, loss, and quiet resilience had lingered with Bahijja since their first encounter.

Widening Gap in Women’s Access to Reproductive Health

According to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), Kano State records 377.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and 59 infant deaths per 1,000 live births—both well above national averages.

With 21% of married women and 36% of unmarried women having an unmet need for family planning, thousands of pregnancies remain unintended, unsafe, or poorly spaced.

Thus, for many women like Maryam in Kano’s remote villages, access to reproductive health care remains a daily struggle—one defined by long distances, deep-rooted cultural norms, and a fragile health system that seldom reaches them.

In Rano, where villages are scattered across unpaved roads and few primary health centres are functional, women often depend on traditional birth attendants or make arduous trips to distant clinics for family planning services.

The outcome is predictable yet tragic: high fertility rates and persistently high maternal and infant mortality figures that continue to place Kano among Nigeria’s most vulnerable states.

MS Ladies Bringing FP Services Home

It was to bridge this gap that MSI Nigeria Reproductive Choices launched the MS Ladies initiative, a nationwide network of over 300 trained, certified, community-based health workers who deliver family planning services directly to women in their homes in remote communities like Fansheri.

In Rano LGA, Bahijja is one of only two MS Ladies serving a population of about 200,000, but their impact is profound. And Maryam, who had suffered repeated stillbirths, is one of their beneficiaries.

“I tried to make my husband understand that family planning doesn’t cause infertility, but he wasn’t ready to listen,” Maryam recalled softly. “After losing three babies, I finally told him that using a contraceptive implant was the way forward.

“I asked him if he wanted our children to live healthy, better lives, and he said yes. So, I told him that getting the implant would help us achieve that—and this time, he agreed. I don’t know what made him change his mind, and I didn’t bother asking. I was just grateful to finally get what I wanted,” Maryam told African Newspage.

Maryam’s story highlights how the MS Ladies model combines community trust, door-to-door outreach, and cultural sensitivity to break barriers in deeply traditional settings.

Changing Lives, One Visit at a Time

Sani Ahmad, MSI’s Social and Behavioural Change Officer in Kano, said there are 100 MS Ladies across Kano State and 312 nationwide, serving remote communities often neglected by mainstream health services.

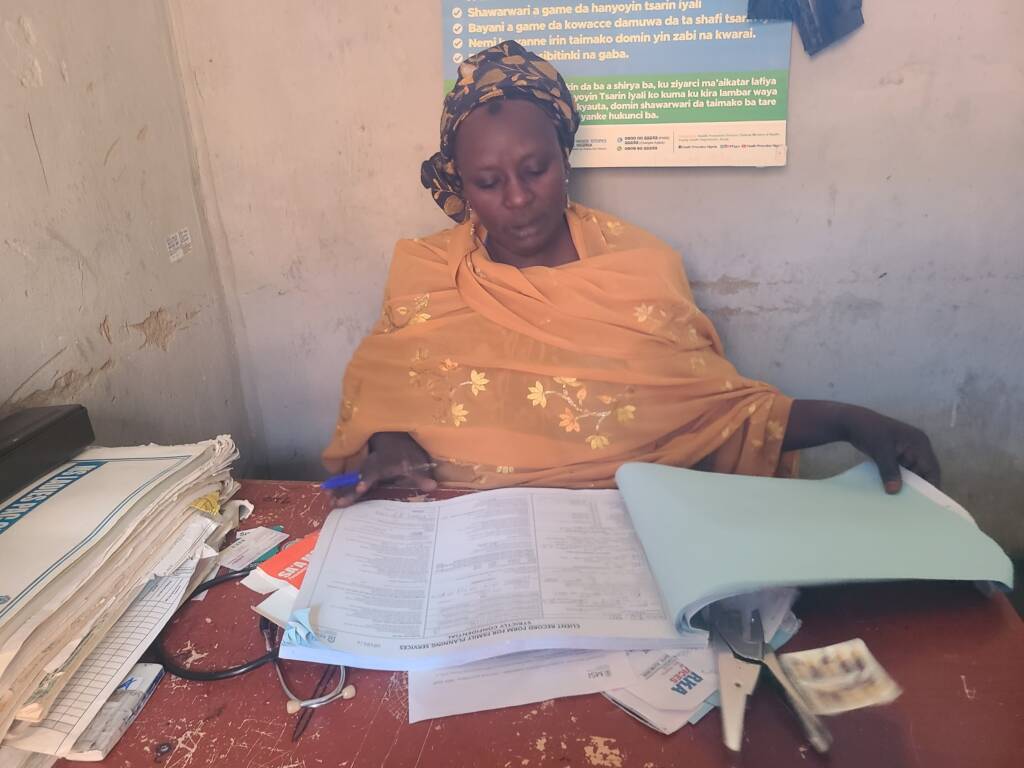

At her Autan Bawo Clinic and Maternity in Rano town, forty-five-year-old Hajiya Ado, the second MS Lady in Rano, sees firsthand the demand for FP services:

“On normal days, I see 5–10 clients. But when I announce a free community in-reach service, up to 50 women show up in one day,” Hajiya noted.

Clients like Maryam and *Ummi Sulaiman (31)—who adopted a contraceptive implant after her second child—say the program has improved their health and family stability.

Government data also shows early signs of progress. The Kano State Primary Healthcare Board has now adopted a Family Planning Strategic Plan (2025–2030), targeting 845,114 women of reproductive age and budgeting ₦500 million for childbirth spacing initiatives.

“We’ve already disbursed ₦50 million to start purchasing our own commodities instead of waiting for donors,” said Zahra’u Ibrahim, Gender/Adolescent and Reproductive Health Specialist at the Board.

This gradual shift from donor dependency to state ownership signals a growing institutional commitment to reproductive health—one that, if sustained, could transform access for women across Kano and beyond.

Why MS Ladies’ Model Works

Experts point to several success factors in the MS Ladies model:

- Community trust: Using local, female health workers improves acceptance.

- Flexibility: Combining home-based and clinic services ensures wider coverage.

- Cultural sensitivity: MS Ladies engage religious leaders and spouses early to reduce resistance.

- Evidence-based adaptation: Data from community in-reach activities inform policy design.

However, sustainability depends on the government’s integration of MS Ladies into public health systems. As MSI’s Ahmad noted, “Our role is to set the footprint for government—not to do all the work.”

For Maryam and others, the impact is deeply personal: “We all want many children, but raising them well is hard. I want mine to live healthy, happy lives,” she said, cradling her baby.

MS Ladies’ Limitations

Despite the progress, the MS Ladies’ initiative is limited by a number of challenges.

- Commodity shortages: “Sometimes women travel far, only to find we’ve run out of stock. It’s heartbreaking,” bemoans MS Lady Hajiya.

- Cultural resistance: Misconceptions about infertility and religious prohibitions persist, discouraging women from seeking services.

- Infrastructure deficits: Poor roads and distance make outreach difficult.

- Scale: With just two MS Ladies covering Rano’s vast area, access remains uneven.

Ameenah bint Muhammad, Executive Director of the Connected Hands for Family Health and Empowerment Initiative (CHAFHEIN), believes systemic change will take time:

“Kano’s population is growing faster than the available service providers. If the gap isn’t closed, women may face delays that lead to more unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions.”

The Bigger Picture

Nigeria’s population is projected to reach 400 million by 2050, growing at an annual rate of 2.5%. Without scaled access to family planning, the country faces mounting pressure on health systems, education, and infrastructure.

The MS Ladies initiative demonstrates how localized, women-led interventions can bridge the gap between national policy and community needs. It offers a replicable model for other states—and a reminder that when women are empowered with information and access, entire communities thrive.

Editor’s Note:

Names marked with an asterisk (*) have been changed to protect identities.

This story was supported by Nigeria Health Watch, in partnership with MSI Nigeria Reproductive Choices and the Family Planning News Network (FPNN), through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.