OP-ED | Who Will Lead AU Commission? Highlights from Mjadala Afrika Debate, By Ueli Staeger

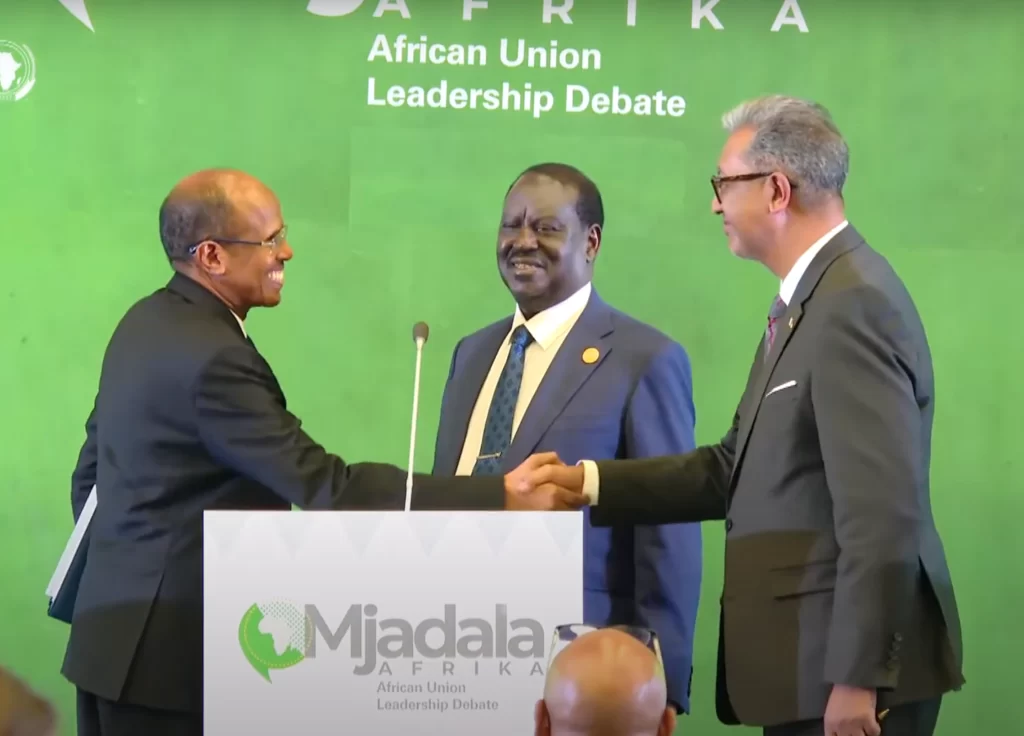

Ueli Staeger argues the success of the recently held Mjadala Afrika, a public debate with candidates for the next Chairperson of the AU Commission, speaks to a broader phenomenon of the AU seeking to re-engage citizens, having lost its popular appeal over partially founded perceptions of ineffectiveness, mismanagement, and stasis.

Candidates have been a lot more public-sphere-focused in this campaign, including in media appearances and specialized think-tank interviews. Leading AU think-tanks Amani Africa and Institute for Security Studies both have been able to conduct in-depth interviews with all candidates, with one exception. Kenya’s Raila Odinga has not granted as many interviews and has also cancelled an appearance at Chatham House on the topic. For an AU that has historically had difficult relations with civil society organizations, activists, businesses, and citizens, Mjadala Afrika is a breath of fresh air.

It bears saying that the event, though styled as a “debate“, did not offer possibilities for interaction between candidates but parallel monologues. The organizers, smoothly delivered in English and French, asked four pre-prepared questions that were all overbearing in scope. For example, candidates were given four minutes to answer why Silencing the Guns in Africa has failed, and how they would address African aspirations for UN Security Council reform. The continent’s very best orator and leader will be unable to address this in only four minutes.

The candidates’ narratives were internally consistent throughout the debate. Richard Randriamandrato (Madagascar) offered meditations on contemporaneous policy principles and a mostly economically driven problem analysis, with less sophistication on AU frameworks than his competitors. Randriamandrato surprised, however, with a few sharp-witted remarks such as that the AU, not Türkiye, should have mediated the Somaliland/Somalia/Ethiopia dispute.

Raila Odinga (Kenya) powerfully rooted his answers in Africa’s independence history but repeatedly stumbled over AU terminology. He also connected most answers to his time as High Representative for Infrastructure Development, not always addressing the questions head-on.

Arguably, the rhetorically most well-rounded candidate was Mahmoud Ali Youssouf (Djibouti), who showcased intimate knowledge of AU frameworks and policies and did not shy away from blaming poor AU performance on “lacking political will among member states“. His in-depth knowledge of AU frameworks and acronyms fleshed out his remarks considerably. Ali Youssouf’s narrative was perhaps most comparable to that of the current AUC Chairperson, Moussa Faki Mahamat, in offering discursive honesty about the AU’s ails while staying constructively optimistic about its aspirations.

A telling round of answers was offered to the (once again expansive) following question on Pan-Africanism and Africa’s geopolitical position: “Pan-Africanism is declining and external powers and internal divisions challenge Africa’s integration efforts. What specific steps will you take to rekindle the spirit of Pan-Africanism on the continent, counter big power politics on the continent, mobilize countries behind a shared agenda, ensure resource reliance and position Regional Economic Communities at the centre of this process?“

Madagascar’s Randriamandrato showed his strongest performance here in calling for a renewal of Pan-Africanism and expressed his hope that “in a few years’ time, foreign military bases in Africa will be a thing of the past“. This remark could be read as a reintegrative rhetorical gesture to West African anti-French sentiment in particular.

Whereas Raila Odinga evaded the question of geopolitics and instead talked about the importance of African economic transformation, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf argued that in a “multi-polarized world“, Africa needs to “be part and parcel of the Global South“, and that economic transformation will enable Africa to meet great powers at eye-level.

On AU reforms, Raila Odinga cited Moussa Faki Mahamat’s statistic of 93% of AU Assembly decisions not being implemented. Odinga also offered a creative idea for alternative funding sources in the use of sovereign funds through which the AU could borrow from its member states. This approach is, unfortunately, incompatible with the AU’s Constitutive Act and its current Financial Rules and Regulations.

Mahmoud Ali Youssouf demonstrated in-depth knowledge of the parameters and key monitoring mechanisms of financial management in AU reforms, including the Golden Rules for financial management and accountability. He demonstrated a clear understanding of the limitations of the Chairperson’s mandate. He even snuck in the only joke of the night about the infamous Skills Audit and Competency Assessment (SACA), still holding up more permanent hires at the AUC, being a hot potato that all candidates hope to have been dealt with by the time they enter office.

Based on the public interviews available and my off-the-record conversations in recent months, countless observers and stakeholders agree that Mahmoud Ali Youssouf emerges as a convincing potential politico-technical manager and leader of the AU Commission. It remains to be seen how member states square these qualifications with inevitable, important, and necessary broader political considerations.

Ueli Staeger is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the University of Amsterdam, in the Political Economy and Transnational Governance research group. This opinion article was originally published as a blog post on Staeger’s blog. The views expressed in it are those of the author and do not necessirily reflect African Newspage’s editorial policy.